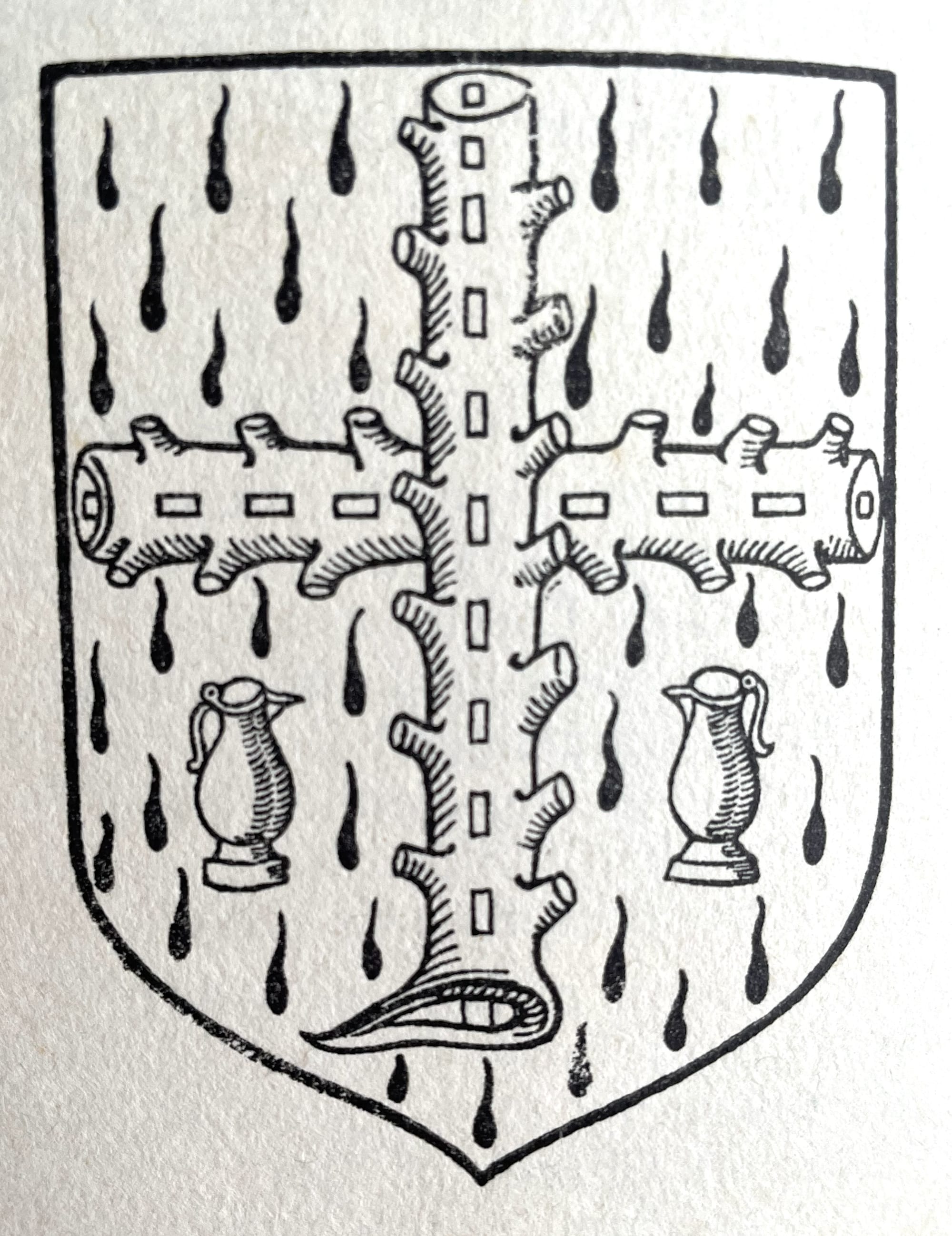

In the feature image above, the heraldic arms attributed to Joseph of Arimathea shows two branches of a thorn tree in the shape of a cross with (presumably) drops of the Savior’s precious blood shed for the salvation of the world.

We here below continue with The Story of Glastonbury by the late Isabel Hill Elder. All emphases and comments within [brackets] are ours, unless otherwise noted. QUOTE:

Whatever may have been the duration of our Lord’s stay in Glastonbury we know that at the age of 30 years He returned to Palestine to begin His ministry, which, for three years, was pursued through suffering and persecution from the Levitical hierarchy, until finally the Chief Priests compassed His cruel death upon the Cross.

Joseph of Arimathea, according to Mosaic Law, claimed the body for burial. Had there been blood brothers this duty would have devolved upon the eldest. The term “brothers” was one of domestic association only for they were the sons of Joseph by a former marriage to a sister-in-law of Zachariah, and were thus full cousins to John the Baptist (see Jerome “Advi Jovianum” libri II compiled in Bethlehem 392 A.D.).

It is significant that Joseph, a Prince of the House of David, and Nicodemus, a high-ranking Levite and “Master in Israel” (John III, 9) were the Divinely appointed bearers of the wounded and lacerated Body from the Cross to the Sepulchre.

After the Crucifixion and Resurrection Joseph of Arimathea, in view of his formal identification of Jesus the Christ, could no longer keep his discipleship a secret, and was, accordingly, with other followers, persecuted by the Jewish hierarchy.

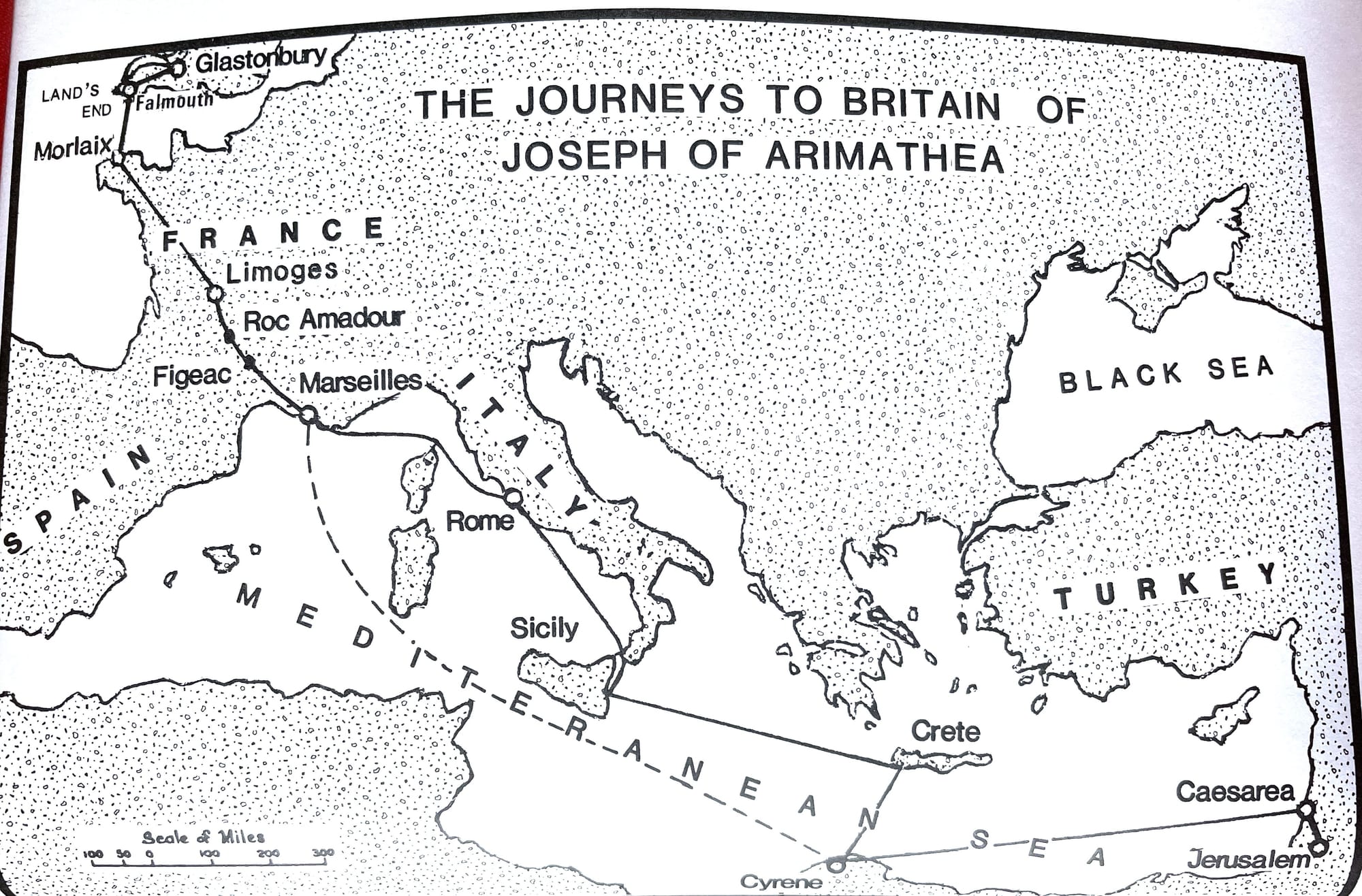

The persecution became more intense after the stoning of Stephen, and many Christians fled to Caesarea on the west coast, prepared to escape by sea if life became unendurable. These Christians were eventually obliged to seek refuge in another land, and sailing along the Mediterranean came to Marseilles.

The names of many of these refugees have come down to us, notably, Joseph of Arimathea, his son Josephes or Josue, and traditionally Joseph was accompanied by eleven disciples, the Bethany family, Zaacheus and others mentioned by Rabanus. (Magdalen College, Oxford, No. 29 in Library Catalogue).

All but the family, disciples and retainers of Joseph of Arimathea settled at various places along the Rhone valley, while the Arimathean party continued their journey to Morlaix where they took ship for south-west Britain, four days’ sail, and following the inlet from the Bristol Channel landed at the Wirral, Glastonbury, about one mile from the Tor. (J. W. Taylor “The Coming of the Saints”, p. 175).

The many legends which have grown around the story of Joseph, mostly from medieval times, when Latin prelates and monks were the historians of Glastonbury, have left in the reader’s mind a picture of poverty, and mud huts, and condescending graciousness on the part of a British king, while the true picture is quite the reverse of these conditions.

In the earliest documentation Joseph is referred to as Joseph de Marmore of Arimathea (see Joseph of Arimathea by the Rev. Smithett Lewis, M.A., p. 94).

[Note: All three books shown in this essay are still available in newer editions from our friends at Artisan Publishers.]

“Mar” is an Eastern term for lord and “more or mawr” signifies “great.” Joseph’s full title, therefore, was “The Great Lord Joseph of Arimathea”, a title in keeping with his birth as a prince of the House of David, and near relative of our Lord, through the virgin mother.

Our St. George is styled Mar George by his body servant, Pasikrates, being of noble birth as the son of the Count of Lydda (Sir Wallis Budge “George of Lydda”, p. 23).

Joseph Marmore and his party would be welcomed and housed temporarily at the Sanctuary or “City of Refuge” and here the king Arviragus (Caractacus) would come over from Caerleon to meet Joseph, whose friend he was.

On this occasion the wealthy Joseph, a “good man and a just”, “honourable counsellor”, “nobilis decurio”, came not on business, but rather in a missionary spirit for since his previous visit his life and outlook had been completely changed by the death and resurrection of his beloved kinsman, Jesus of Nazareth, whose secret disciple he was throughout our Lord’s earthly ministry.

The eleven disciples of Joseph of Arimathea are not identifiable with our Lord’s disciples who in obedience to His command went into “all the world” to preach the Gospel of the Kingdom; that is the Roman world, the same “world” that was taxed at the time of the birth of our Lord.

Moreover, the disciples, according to the Saviour’s command, continued for the space of twelve years preaching only to the twelve tribes of the Hebrews.” (Rabanus, chapter 36).

The immediate outcome of the Arimathean mission was the forging of four significant links between Glastonbury and the Holy Land, and the undeniable fulfilment of prophecy. The eleven disciples or companions of Joseph would, of necessity, represent each a tribe in Israel, Joseph of the House of David representing Judah, and the others the remaining tribes.

The first notable act of the king, Arviragus, was to bestow upon these “Judean refugees” XII hides of land free of tax. It is stated in the Liber de Soliaco (1619 A.D.) that at Glastonbury itself 1 hide of land=160 acres.

With this land grant a document was furnished setting forth the legal aspect of the gift, which gave the recipients many British concessions including right of citizenship and all the privileges accorded the Druidic hierarchy. Every Druid was entitled to one hide of land, free of tax, freedom to pass unmolested from one district to another in time of war, and many other privileges.

This grant of XII hides of land is recorded in Domesday Book (Domesday Survey, folio p. 249b).

There was more to this grant of land than appears on the surface; its deep significance has never been fully realized, and goes back to about 1000 B.C. when the Lord God of Israel informed David, the king, that “his throne shall be established for evermore” (I Chron. XVII, 14) and in verse 9, “I will appoint a place for my people Israel and they shall dwell in their place, and shall be moved no more; neither shall the children of wickedness waste them any more as at the beginning.”

At this time Israel was in full possession of the Promised Land; this they had received under the Old Covenant made with their forefathers. The “Appointed Place” promised to David had no time specification. “I will appoint a place for my people Israel.”

All the prophets point to this place as “the isles” situated north-west of Palestine. This place, the second Promised Land, Israel could not receive officially until the New Covenant was made. When our Lord, at the Last Supper, held the cup in His hand and uttered the words “This cup is the New Covenant in my blood” He also declared, “I appoint unto you a kingdom.”

With these utterances our Lord inaugurated the New Covenant. After the Resurrection, and Ascension, when Joseph Marmore of Arimathea came to the British Isles (Brith [Hebrew word] = Covenant) with his disciples and received the XII hides of land, that transaction constituted the handing over, in token, of the “Appointed Place” under the New Covenant.

Thus was forged the first official link between Britain and the Holy Land and the spot chosen was the then sacred Glastonbury with its Levitical services to be replaced very soon by Christian worship.

The Arimathean party of Christian Israelites were received at Glastonbury as “Judean refugees,” in old Latin, “quidam advanae” = certain strangers; in later Latin Culdich, Anglicised Culdees.

They proceeded with the full consent of the king and the Druidic hierarchy to introduce the Gospel of Christ by building a church, a wattle church, to precisely the dimensions of the Tabernacle of old.

To the modern mind a wattle building was of the most humble kind, even William of Malmesbury (1143 A.D.) in writing of the Ealde Church (Old Church) says: - “Of wattle work at first, it savoured somewhat of heavenly sanctity even from its very foundation, and exhaled it all over the country, claiming superior reverence, though the structure was mean.” In this comment on the structure Malmesbury was entirely in error.

The walls were built in precisely the same way in which it was the custom to build kings’ palaces. Howel, King of Wales, built a house of white twigs to retire to whenever he came to hunt in South Wales, which was called Ty Gwyn = The White House. Castles, in those days, were built of the same material, as we learn from Giraldus Cambrensis, who, speaking of Pembroke Castle says: “Arnulphus de Montgomery in the days of Henry I built that small castle of twigs and slight turf.”

These wattle buildings thatched with reeds, often painted or washed with lime withstood the most severe weather. The wattle church at Glastonbury was built of timber pillars and framework doubly wattled inside and out and thatched with reeds as the mode then was. Such also was the primitive Capitol of Rome (Ovid “Faesti ad Fest Roma”).

The wattle church at Glastonbury became known as the Culdee Church, or Church of the Refugees; this title adhered to the early Christian Church in Britain for many centuries, and even in medieval times the Culdees worshipped in a corner of the Latin Church, Rome being unable to entirely suppress them. Eventually they became the first heralds of the Reformation.

The second of the four links with the Holy Land concerns the custom in ancient times, of the purchaser or other claimant in land transactions, placing upon the land a termon (a stone cut roughly in the form of a cross) or alternatively planting a tree.

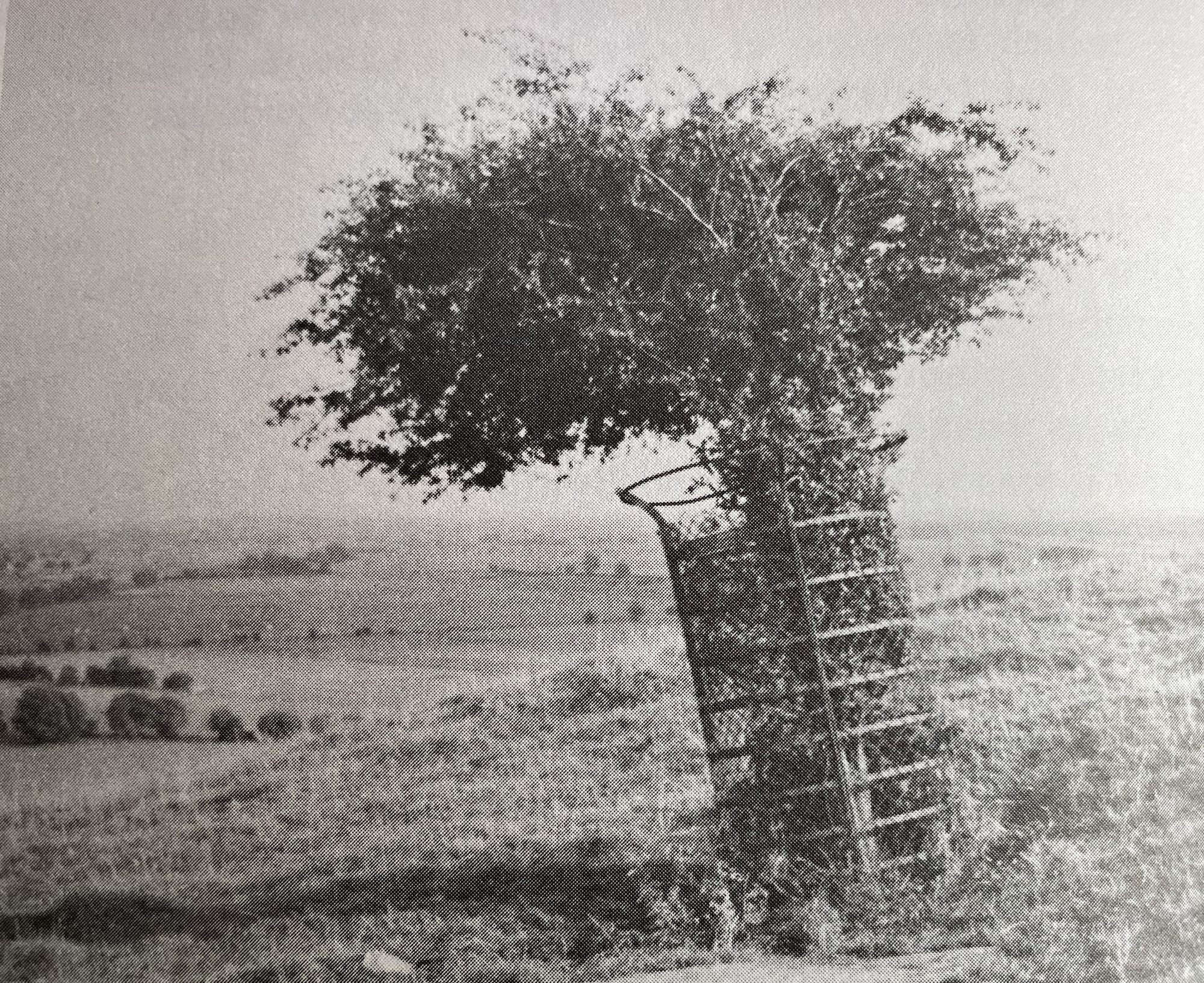

The latter method was adopted by Joseph of Arimathea soon after his arrival at Glastonbury, for the staff Joseph carried he thrust into the ground on the Wirral.

This could not have been his own staff for, according to an unwritten law in Israel the father must pass on his staff to his eldest son or appointed heir, and was often made a ceremonious occasion at the dying couch as instanced by the patriarch Jacob passing on his staff to Joseph, his appointed heir (Gen. XLVII, 31. Staff mistranslated “bed’s head”). See Heb. XI, 21.

The staff planted by Joseph Marmore would be our Lord’s staff for Joseph as His nearest male relative had the disposal of our Lord’s belongings; no doubt Joseph had been instructed by our Lord as to the disposal of the staff and perhaps chose the spot where it should be planted.

The thorn staff like Aaron’s rod, budded and blossomed (Num. XVII, 8), and eventually grew into a beautiful tree, becoming widely known as “The Sacred Thorn.” In this way an unmistakable link was forged with the Holy Land under the New Covenant, our Lord Himself claiming the “Appointed Place” with His staff. The Wirral must, of necessity, have been part of the XII hides of land, the promised land in token.

The Holy Thorn flourished at Glastonbury through every change of government and religious domination until the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII, when an irate Puritan, in the belief that the Thorn was an object of idolatry in the Latin Church, with mistaken zeal and lack of knowledge almost completely hacked it down.

This tree has wonderful vitality and from the mutilated tree a tiny shoot appeared and was carefully tended until it grew into a beautiful tree laden with blossom in the spring, and again from October to Christmas.

The very ancient custom of sending a spray of the flowers to the Sovereign at Christmas is still maintained; it is the privilege of the Vicar of St. John’s, Glastonbury to dispatch the flowers.

There is a fine specimen of the Thorn in the Abbey grounds, and another in the garth of St. John’s Church. The flowers on the Thorn are at the height of their perfection on old Christmas Day. Pere Cyprian Gamache, Roman Catholic Confessor to Queen Henrietta Maria, tells how Charles I chaffed him because the miraculous tree contradicted the Pope by blossoming on old Christmas Day and not on the new. (Coulburn “Court and Times of Charles I”, vol. II, p. 417).

(To be continued.)

~END~